Key Parallels

- Protectionist Approach: Both Nixon and Trump used tariffs as economic weapons to force trading partners to renegotiate terms. Nixon implemented a 10% import tariff, while Trump has introduced his own tariff regime.

- Trade Deficit Focus: Both presidents were motivated by reducing the US trade deficit. Nixon targeted Japan and Germany; Trump’s policies similarly target major trading partners with significant US trade imbalances.

- Domestic Political Considerations: Both used economic nationalism as a political tool, with Treasury Secretary Connally’s quote to Nixon being particularly revealing: “all foreigners are out to screw us, and it’s our job to screw them first.”

- De-anchoring Financial Systems: Nixon’s removal of the dollar from the gold standard fundamentally changed the global financial system. Trump’s tariffs similarly risk destabilizing established trade frameworks and relationships.

- Pressure on the Federal Reserve: Nixon pressured the Fed for expansionary monetary policy to offset economic shocks from his policies. Trump has similarly been known to pressure the Fed regarding interest rates.

- Treatment of Allies: Both administrations showed a willingness to impose economic penalties, even on close allies. The article notes Canada’s experience under Nixon as an example.

Implications for Asia and Singapore

- Economic Uncertainty: Nixon’s policies led to global economic instability. For Asia, Trump’s tariffs create similar uncertainty, potentially disrupting established supply chains and trade relationships.

- Financial Innovation: The Nixon shock catalyzed financial innovations like FX futures. Asian financial centers like Singapore might see opportunities to develop new financial instruments to hedge against similar uncertainties.

- Shift to Alternative Markets: Just as Nixon’s policies pushed activities from banks to bond markets, Trump’s tariffs might accelerate Asian countries’ efforts to diversify away from US-dependent trade systems.

- Regional Integration: The article notes how the Nixon shock eventually led to the creation of the euro. Trump’s policies might similarly accelerate regional economic integration in Asia, potentially strengthening organizations like ASEAN or RCEP.

- Singapore’s Position: As an open, trade-dependent economy and financial hub, Singapore faces both challenges and opportunities:

- Challenges: Vulnerability to trade disruptions and economic volatility

- Opportunities: Potential to serve as a neutral financial hub for transactions avoiding US jurisdiction

- Hedge Against Dollar Dominance: Asian economies, including Singapore, might accelerate efforts to reduce dollar dependence, potentially increasing the role of other currencies in regional trade.

- Long-term Structural Changes: Just as the Nixon shock had effects that “rippled through the decades,” Trump’s policies could catalyze long-term structural changes in Asia’s financial systems and trade relationships.

Singapore’s heavily trade-dependent economy makes it particularly sensitive to global trade disruptions. However, its strong financial sector and strategic position could allow it to adapt and potentially benefit as regional trade and financial patterns evolve in response to these changes.

Implications of US Tariffs and Isolationism for Singapore and Asia

Direct Economic Impact

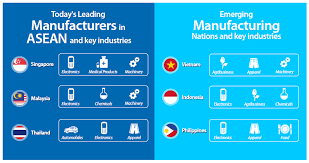

- Export Vulnerability: Singapore’s open, trade-dependent economy (trade is over 300% of GDP) makes it particularly vulnerable to US tariffs. Key export sectors like electronics, chemicals, and precision equipment could face direct tariff impacts.

- Supply Chain Disruption: Many Asian economies, including Singapore, are deeply integrated into global supply chains with the US as an end market. Tariffs force painful and costly supply chain restructuring.

- Trade Diversion: Some Asian manufacturers might relocate production to avoid US tariffs, potentially benefiting countries not directly targeted. Singapore could potentially capture some high-value services in this restructuring.

- Reduced Growth: The IMF and other forecasters have warned that sustained US tariffs and trade conflicts could reduce Asian GDP growth by 0.5-1.5 percentage points, depending on severity and duration.

Strategic and Long-term Implications

- Accelerated Regional Integration: US isolationism is likely to accelerate Asian economic integration. Frameworks like RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) are becoming more important as alternatives to US-centric trade.

- Financial System Evolution: Similar to how the “Nixon shock” catalyzed financial innovation, US isolationism could accelerate the development of Asian financial infrastructure less dependent on the dollar:

- Greater use of local currencies in intra-Asian trade

- Development of alternative payment systems

- Singapore’s opportunity to strengthen its position as a financial hub

- Investment Patterns: US isolationism may redirect investment flows within Asia. Singapore, with its stable governance and strong financial system, could benefit as a safe haven for regional investment.

- China’s Expanding Influence: A US retreat creates space for China to expand its economic and geopolitical influence. For Singapore, this means carefully balancing relations between these powers.

Singapore-Specific Considerations

- Diplomatic Challenge: Singapore’s traditional role of balancing US and Asian relationships becomes more complex. Its value as a neutral meeting ground may increase.

- Economic Diversification Pressure: This reinforces Singapore’s need to diversify trading partners and economic activities beyond traditional manufacturing and US markets.

- Financial Sector Opportunity: Singapore could position itself as a key center for trade financing and financial services that facilitate transactions avoiding US jurisdiction.

- Strategic Industries: Singapore might need to protect and develop capabilities in strategic sectors that could be disrupted by trade conflicts.

- Innovation Focus: Accelerated investment in innovation and digitalization to maintain competitive advantage even as traditional trade advantages erode.

Regional Responses

- Alternative Trade Agreements: ASEAN, RCEP, and potentially CPTPP gain importance as counterweights to US isolationism.

- Currency Management: Asian central banks, including Singapore’s MAS, face challenges managing currency stability amid increased volatility.

- Policy Coordination: Greater incentive for Asian economies to coordinate policy responses to US actions, potentially strengthening regional institutions.

The ultimate impact depends on whether US isolationism proves temporary or represents a fundamental shift in US economic policy. History suggests that even “temporary” measures like Nixon’s can trigger lasting structural changes in global economic relationships. Singapore’s adaptability and strong institutions position it better than many to navigate these challenges, but significant strategic adjustments will be necessary.

Long-Term Strategic Adaptation to Multipolar Shift for Singapore and Asia

Diplomatic Strategies

- Strategic Hedging

- Cultivate meaningful security and economic relationships with all major powers (US, China, India, EU)

- Avoid exclusive alignment with any single power.

- Develop specialized diplomatic expertise in managing complex, sometimes contradictory relationships

- Minilateral Diplomacy

- Foster smaller, flexible groupings of like-minded states beyond traditional blocs.

- Create issue-specific coalitions to address targeted concerns (climate, supply chains, digital governance)

- Strengthen Singapore’s role as a neutral convener for sensitive diplomatic engagements.

- Institutional Capacity Building

- Strengthen ASEAN’s institutional capabilities and cohesion

- Advocate for the modernization of international institutions to reflect multipolar realities

- Develop diplomatic corps with more profound regional expertise and technological understanding

Economic Adaptation

- Trade Architecture Diversification

- Advance multiple overlapping trade frameworks (RCEP, CPTPP, bilateral FTAs)

- Develop specialized economic corridors with strategic partners

- Create redundancy in critical supply chains and market access

- Financial System Resilience

- Reduce excessive dependence on dollar-based financial infrastructure

- Expand local currency settlement mechanisms for intra-Asian trade

- Position Singapore as a neutral financial intermediary between competing systems

- Strategic Sector Development

- Identify and cultivate industries impervious to great power competition

- Develop sovereign capabilities in critical technologies and resources

- Focus on sectors where Singapore can maintain a competitive advantage regardless of geopolitical shifts

Knowledge and Innovation Focus

- Education System Adaptation

- Develop expertise in multiple cultural and political systems

- Emphasize adaptability, cross-cultural intelligence and strategic thinking

- Build capacity to operate effectively across competing technical standards

- Research Priorities

- Cultivate expertise in technologies with multiple applications across competing ecosystems.

- Focus on adaptable innovation that can serve diverse markets and standards

- Develop research partnerships across geopolitical dividing lines

- Digital Infrastructure

- Create systems capable of interfacing with multiple competing technological standards.

- Position Singapore as a digital translation layer between competing ecosystems

- Maintain technological sovereignty in critical systems

Regional Coordination Mechanisms

- Economic Integration

- Deepen intra-Asian economic integration to create resilience against external shocks.

- Strengthen ASEAN economic community initiatives.

- Develop regional mechanisms for crisis coordination independent of power influence.

- Security Architecture

- Establish more robust regional security dialogue mechanisms

- Develop a principles-based approach to maritime and territorial disputes

- Create crisis prevention and management protocols

- Standards Development

- Lead development of regional standards and norms in emerging areas (digital economy, biotech)

- Position Singapore as a standards bridge between competing systems

- Build consensus on baseline regulatory frameworks

The fundamental principle behind these strategies is developing what might be called “strategic optionality” – maintaining maximum flexibility and adaptability in an uncertain multipolar landscape while preserving core interests and values. Singapore’s historical success has come from its adaptability and pragmatism – qualities that will be even more essential in navigating the complex multipolar world emerging before us.

Shifts in ASEAN Diplomacy to Adapt to a Multipolar World

Evolution of ASEAN’s Diplomatic Approach

From Consensus to Flexible Consensus

- Traditional Consensus Model

- ASEAN’s historical “consensus at all costs” approach has often led to paralysis on contentious issues

- The South China Sea disputes exposed limitations when members have divergent interests.

- Inability to issue joint communiqués (like Phnom Penh 2012) damaged credibility.

- Emerging Flexible Consensus

- Growing willingness to acknowledge “agreement to disagree” on specific issues

- Development of “ASEAN minus X” and “ASEAN plus X” formulations to allow progress despite disagreements

- Selective use of Chair’s statements when formal consensus proves impossible

From Non-Interference to Constructive Engagement

- Limits of Traditional Non-Interference

- Once sacrosanct principle now increasingly strained by transnational challenges.

- Internal issues (Myanmar crisis, environmental disasters) with clear regional implications

- Calibrated Constructive Engagement

- More nuanced approach acknowledging internal-external connections

- Development of structured dialogue mechanisms for sensitive issues

- Greater willingness to privately engage on domestic matters with regional implications

Strategic Adaptations

From Neutrality to Strategic Autonomy

- Beyond Passive Equidistance

- Moving from neutrality defined as “not taking to proactive strategic autonomy”

- Developing ASEAN’s independent voice on global issues

- Articulating distinct regional positions on key questions (Ukraine, Middle East, etc.)

- Active Hedging Strategies

- More sophisticated collective engagement with major powers

- Development of differentiated approaches to various partnerships

- Building stronger intra-ASEAN coordination before major power engagements

From Reaction to Agenda-Setting

- Proactive Norm Development

- Taking initiative on emerging issues before external frameworks are imposed

- ASEAN Digital Economy Framework as an example of getting ahead of regulatory fragmentation

- Developing indigenous approaches to AI governance, digital currencies, etc.

- Institutional Innovation

- Reform of ASEAN Secretariat to enhance coordination capabilities

- Development of rapid response mechanisms for crises

- Creation of specialized centers of excellence on strategic issues (cybersecurity, climate resilience)

Diplomatic Architecture Innovations

Expanding Dialogue Mechanisms

- Beyond Traditional Partners

- Systematic engagement with emerging powers beyond traditional dialogue partners

- Development of structured interactions with Global South groupings (African Union, etc.)

- Creation of specialized technical dialogues on critical issues

- Minilateral Forums

- Increasing use of smaller, flexible groupings within and alongside ASEAN

- Development of issue-specific coalitions (Mekong subregion, maritime security, etc.)

- Strategic use of “ASEAN Plus” configurations tailored to specific challenges

Strengthening External Voice

- Coordinated International Representation

- More unified ASEAN positioning at UN, G20, and other global forums

- Development of rotating ASEAN spokesperson roles on key issues

- Enhanced mechanisms for rapid position coordination during global crises

- Strategic Communications

- More sophisticated articulation of ASEAN perspectives to global audiences

- Development of shared strategic narratives on regional security and prosperity

- Enhanced public diplomacy capabilities coordinated across member states

Challenges to Adaptation

- Sovereignty Sensitivities

- Lingering reluctance to empower supranational mechanisms

- Varying comfort levels with institutional evolution across member states

- Political constraints on delegation of authority to regional mechanisms

- Capacity Disparities

- Significant gaps in diplomatic resources and capabilities among members

- Uneven ability to implement sophisticated diplomatic strategies

- Need for targeted capacity building for smaller states

- External Pressures

- Risk of fragmentation through competing external initiatives

- Challenge of maintaining cohesion when members face divergent external pressures

- Need for institutional buffers against divide-and-rule approaches

The trajectory of ASEAN diplomacy shows incremental but meaningful evolution beyond its founding principles without abandoning them entirely. Rather than a dramatic rejection of core approaches like consensus and non-interference, we’re seeing their thoughtful reinterpretation for a more complex geopolitical landscape. Singapore, with its diplomatic capabilities and strategic perspective, is well-positioned to guide this evolution while ensuring that ASEAN remains central to regional architecture.

The Crucial Parallel Between Nixon’s Era and Today’s Context

The most fundamental parallel between Nixon’s 1971 economic actions and today’s situation is the attempted management of American relative decline through economic nationalism.

In both periods, we see:

- Relative Power Shift: In Nixon’s era, the US was experiencing its first significant relative economic decline since WWII. Germany and Japan had rebuilt impressively, and the US share of global GDP was shrinking. Similarly, today’s world is characterized by China’s rise and broader economic multipolarity.

- Domestic Economic Pressures: Both periods feature significant domestic economic anxieties. Nixon faced stagflation and growing concerns about manufacturing job losses. Today’s America similarly confronts deindustrialization, wage stagnation for many workers, and growing inequality.

- Monetary System Tension: The Nixon shock fundamentally altered the post-WWII Bretton Woods system. Today, de-dollarization efforts, alternative payment systems, and digital currency developments are increasing the challenges to dollar hegemony.

- Unilateral Tools to Address Structural Issues: In both cases, US administrations deployed unilateral economic measures (tariffs, dollar policy) to address deep structural imbalances in the global economy that arguably required multilateral solutions.

- Economic Tools for Geopolitical Ends: Both administrations used economic levers as extensions of geopolitical strategy. Nixon’s economic nationalism coincided with his opening to China to counterbalance the Soviet Union. Today’s economic measures are inseparable from broader geopolitical competition.

The most significant lesson from this parallel is that short-term economic nationalism often accelerates the very trends it attempts to counteract. Nixon’s actions, while providing temporary relief for domestic political pressures, ultimately hastened changes in the global financial architecture that reduced American centrality. Today’s tariffs and economic nationalism similarly risk accelerating the development of alternative economic arrangements that may ultimately reduce US influence.

For Asia and Singapore specifically, both periods represent moments when the established economic order faced significant reconfiguration, requiring strategic adaptation rather than mere tactical responses. In the 1970s, this led to significant economic model shifts across Asia. Today’s challenge may require equally fundamental rethinking of development models that have been predicated on US-centric trade and financial systems.

The parallel between Nixon’s corruption and the present context does add another dimension worth considering.

Nixon’s presidency ended with the Watergate scandal and his resignation to avoid impeachment, though he wasn’t actually convicted in a criminal sense (he received a presidential pardon from Gerald Ford). The corruption that defined the end of his presidency occurred during a period of significant economic and geopolitical transition for the United States.

This parallel could be viewed as concerning for several reasons:

- Institutional Stress: Both periods feature significant stress on democratic institutions. Nixon’s corruption emerged during a time when American institutions were already under strain from economic challenges, social upheaval, and geopolitical competition. Today’s institutions face similar multifaceted pressures.

- Crisis Governance: Corruption often thrives in environments where normal governance processes are bypassed in the name of addressing crises. Both Nixon’s era and today feature appeals to exceptional measures to address perceived national emergencies.

- Economic Nationalism and Democratic Backsliding: There appears to be a correlation between aggressive economic nationalism and challenges to democratic norms. Nixon’s “America First” approach to economic policy paralleled his administration’s erosion of democratic norms, similar to patterns we see in various countries today.

- Trust Deficit: Nixon’s corruption further eroded public trust in government at a time when effective governance was particularly crucial. Today’s challenges similarly require public trust for practical solutions.

For Asia and Singapore, this parallel suggests that the economic adjustments needed to navigate a multipolar world may be complicated by governance challenges in significant powers. This reinforces the need for robust regional institutions and frameworks that can provide stability even when major powers experience internal turbulence.

The historical pattern suggests that periods of relative decline and economic restructuring create particular vulnerabilities for democratic governance. This doesn’t make any particular outcome inevitable, but it does highlight the importance of institutional resilience during periods of significant economic transition.

Asian Trade Implications

- Regional Trade Architecture

-

- RCEP Considerations: The Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (which includes China and many Southeast Asian nations) might provide some framework for managing these issues but doesn’t specifically address strategic material restrictions.

-

- ASEAN Response: The Association of Southeast Asian Nations may need to develop a coordinated approach to rare earth supply security to protect regional manufacturing interests.

-

- New Supply Partnerships: Japan’s investments in Australian rare earth mining could serve as a model for new regional cooperation, potentially involving Singapore as a processing or logistics hub.

Economic Security vs. Efficiency

The rare earth restrictions highlight a fundamental tension in Asian trade patterns:

-

- Economic Efficiency: Traditional supply chains optimized for cost and efficiency rely heavily on Chinese processing capacity.

-

- Economic Security: Countries are increasingly prioritizing secure access over pure efficiency, potentially leading to redundant but more resilient regional supply chains.

Outlook for Singapore and Asian Trade

The rare earth restrictions represent both a challenge and an opportunity for Singapore and the broader Asian trading system.

- Short-term Disruption: Some manufacturing sectors will face higher supply uncertainty in the immediate term.

- Medium-term Adaptation: Singapore is well-positioned to adapt through its strong governance, financial resources, and technological capacity.

- Long-term Reconfiguration: Asian trade patterns are likely to evolve toward more resilient, potentially regionalized supply chains for critical materials.

Singapore’s traditional strengths in navigating complex international trade environments, combined with its advanced manufacturing capabilities, position it relatively well to manage these challenges compared to more resource-dependent economies in the region. However, developing strategic approaches to rare earth supply security will likely become an increasingly important policy priority.

Analysis: Rare Earth Restrictions – Long-term Fallout and Solutions for Singapore

Long-Term Fallout for Singapore

Economic Ripple Effects

-

- Supply Chain Disruption: As a small, export-oriented economy deeply integrated into global value chains, Singapore will feel secondary effects from U.S.-China trade tensions even without being directly targeted. If key U.S. technology firms face production constraints due to rare earth shortages, this affects their global operations, including Singapore-based facilities or partnerships.

-

- Tech Sector Vulnerability: Singapore’s growing semiconductor, biomedical, and precision engineering sectors rely on consistent access to the same rare earth materials now being restricted. As global prices rise and availability becomes uncertain, Singapore’s manufacturing competitiveness could be affected.

-

- Re-export Complications: The article mentions China’s ability to track where its rare earths end up. It notes that it might crack down on third countries it suspects are re-exporting to America. As a central trading hub, Singapore could face scrutiny over its rare earth imports if China believes they might be destined for eventual U.S. use.

Strategic Position

-

- Forced Alignment Pressures: If rare earth trade becomes increasingly politicized, Singapore may face implicit pressure to “choose sides” in securing access to these materials, challenging its traditional balanced diplomatic approach.

-

- Regional Rebalancing: As countries like Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan also seek to secure their rare earth supply chains, Singapore’s relative position in regional tech manufacturing hierarchies could shift based on who secures the most stable supply arrangements.

-

- Investment Patterns: Long-term uncertainty in rare earth access could redirect investment flows, potentially benefiting Singapore if seen as a stable environment or harming it if material access becomes a decisive factor in manufacturing location decisions.

Potential Solutions for Singapore

Diplomatic and Trade Approaches

-

- Multi-directional Engagement: Singapore should maintain and strengthen diplomatic ties with both China and rare earth alternative sources (Australia, Vietnam, Brazil), positioning itself as a neutral partner rather than aligned with any particular bloc.

-

- Regional Coordination: Lead ASEAN initiatives to develop a regional rare earth security strategy, potentially including collective purchasing agreements or shared processing facilities.

-

- Trade Agreement Provisions: Advocate for including critical material access guarantees in future trade agreements, which would reduce vulnerability to unilateral restrictions.

Economic and Industry Solutions

-

- Strategic Stockpiling: Develop a national stockpile of critical rare earth materials to insulate Singapore’s industries from short-term supply disruptions and price spikes.

-

- Processing Investment: Given Singapore’s strong chemical industry base, invest in developing rare earth processing capabilities that could serve regional needs while adding value beyond pure trading activities.

-

- Manufacturing Adaptation: Support local manufacturers in adapting product designs to reduce rare earth dependence, following Japan’s successful model after its 2010 experience with Chinese restrictions.

- Technology and Research Initiatives

-

- Urban Mining Development: Expand Singapore’s existing electronic waste recycling capabilities to specifically target rare earth recovery, creating a secondary domestic source.

-

- Material Substitution Research: Fund targeted research at universities and A*STAR to develop alternatives to rare earth materials in key applications relevant to Singapore’s manufacturing base.

-

- Process Innovation: Develop more efficient rare earth utilization technologies that could be licensed globally, creating a new expertise area for Singapore while addressing broader supply concerns.

Long-term Strategic Positioning

Knowledge Economy Focus

Singapore can leverage this challenge to accelerate its transition from a manufacturing-dependent to a knowledge-based economy by:

-

- Developing Expertise: Building specialized knowledge in critical material supply chain management that can be exported as a service.

-

- Creating Standards and Certification: Establishing Singapore as a trusted neutral verifier for rare earth sourcing and processing sustainability.

-

- Financial Products: Creating specialized trading and hedging instruments for rare earth materials through Singapore’s financial sector.

Regional Hub Evolution

-

- Alternative Processing Center: Position Singapore as the “clean” and politically neutral alternative to Chinese rare earth processing for countries that do not want to develop domestic capacity.

-

- Supply Chain Orchestration: Build on Singapore’s logistics strengths to become the coordination center for diversified rare earth supply chains.

-

- Technological Bridge: Facilitate technology transfer between Western mining operations and Asian manufacturing toTermrove rto Termrovere earth self-sufficiency.

Outlook and Timeline

Short Term (1-2 years)

-

- Price increases and uncertainty as markets adjust

-

- Opportunity for Singapore to begin strategic stockpiling at still-maTermable prices

-

- Initial assessments of manufacturing vulnerability

Medium Term (3-5 years)

-

- New supply sources begin coming online globally

-

- Singapore would need to establish its role in newly forming supply chains

-

- ITermal returns on research investments in alternatives and recycling

Long Term (5-10+ years)

-

- Fully diversified global rare earth supply chains

-

- Potential for significantly reduced dependence through technological advancement

-

- New equilibrium in trading relationships with more resilient but potentially higher-cost structures

The rare earth restrictions represent a significant long-term challenge that will reshape global high-tech manufacturing. For Singapore, they present both risks to existing economic models and opportunities to develop new capabilities that align with its strengths in logistics, finance, and high-value manufacturing. By taking a proactive approach focused on diversification, innovation, and regional coordination, Singapore can potentially emerge stronger despite the initial disruptions.

Implications of Rare Earth Restrictions for Singapore’s Semiconductor Sector

Direct Material Dependencies

Singapore’s semiconductor sector faces specific vulnerabilities related to rare earth restrictions:

-

- Critical Manufacturing Inputs: Though rare earth metals are not used in large quantities in semiconductor production, they are essential for specific processes and equipment:

- Cerium oxide is used for the precision polishing of silicon wafers

- Europium, terbium, and yttrium are utilized in phosphors for inspection equipment

- Gadolinium and erbium are found in specialized optical components for lithography systems

-

- Samarium-cobalt magnets are used in precision positioning systems

- Critical Manufacturing Inputs: Though rare earth metals are not used in large quantities in semiconductor production, they are essential for specific processes and equipment:

-

- Testing and Packaging Equipment: Singapore specializes in semiconductor assembly and test operations, where equipment often relies on rare earth magnets for precise movements and positioning.

-

- Manufacturing Environment Systems: Advanced clean room facilities depend on high-efficiency motors and pumps that often contain rare earth magnets.

Industry-Specific Consequences

Supply Chain Vulnerabilities

Competitive Position

-

- Regional Rebalancing: Singapore’s semiconductor sector competes with facilities in Taiwan, South Korea, and increasingly, China. Differential access to rare earths could shift competitive dynamics, particularly if China-based facilities maintain preferential access.

-

- Customer Priorities: Major customers like Apple, Qualcomm, and AMD might prioritize manufacturing partners based on supply chain resilience, potentially benefiting or harming Singapore’s position depending on its adaptation strategy.

-

- Investment Attractiveness: Singapore’s appeal for new semiconductor investments could be affected if materials access becomes a significant concern relative to other locations.

Strategic Opportunities

Manufacturing Innovation

-

- Process Adaptation: Singapore’s semiconductor firms could lead in developing manufacturing processes that reduce rare earth dependence, creating intellectual property that could be licensed globally.

-

- Equipment Modification: Potential to develop specialized equipment modifications that maintain performance while using alternative materials, positioning Singapore as a solutions provider.

-

- Design-for-Resilience: Opportunity to establish design services that create semiconductor products specifically engineered to minimize vulnerable material dependencies.

Industry Positioning

-

- Specialty Focus: Singapore could strategically concentrate on semiconductor applications less dependent on rare earths, such as specific memory, power, or analog products.

-

- Vertical Integration: Consider strategic investments in upstream processing capabilities for critical materials used in semiconductor manufacturing.

-

- Certification Development: Create verification systems for tracking rare earth materials throughout the semiconductor supply chain, addressing increasing customer demands for supply transparency.

Policy and Industry Response Options

Immediate Mitigation Strategies

-

- Critical Material Inventory Management: Support semiconductor firms in developing enhanced inventory strategies for rare earth-dependent components and consumables.

-

- Supply Chain Mapping: Conduct comprehensive analysis of rare earth dependencies throughout the semiconductor manufacturing process to identify and prioritize vulnerabilities.

-

- Alternative Supplier Development: Actively cultivate relationships with rare earth suppliers outside China, potentially leveraging Singapore’s strong diplomatic position.

Long-term Structural Solutions

-

- Recycling Ecosystem Development: Build specialized rare earth recycling capabilities focused on semiconductor manufacturing waste and end-of-life equipment.

-

- Research Partnerships: Form targeted research collaborations between semiconductor firms, universities, and A*STAR to develop rare earth alternatives for specific semiconductor applications.

-

- Supply Chain Resilience Incentives: Implement policy incentives for semiconductor firms that demonstrate enhanced supply chain resilience through material diversification.

Industry Outlook

Scenario Analysis

-

- Base Case: Temporary disruption followed by higher but manageable costs as supply chains adapt over 3-5 years.

-

- Moderate Impact: Sustained competitive disadvantage for Singapore facilities vs. China-based operations, requiring significant adaptation investments.

-

- Severe Disruption: Critical tool shortages affecting production capacity and ability to maintain current technology roadmaps, potentially leading to market share loss.

Long-term Perspectives

The rare earth restrictions challenge Singapore’s current semiconductor industry structure and offer an opportunity to develop new capabilities that enhance its position in the global semiconductor value chain. While the immediate focus will be on securing supply continuity, the longer-term strategic response should address fundamental questions about Singapore’s semiconductor industry positioning in a world of increasing resource nationalism and fragmented supply chains.

Singapore’s historical strengths in adaptation, strong governance, and high-value manufacturing position its semiconductor sector to potentially emerge stronger from this challenge if it can successfully develop new approaches to material dependency management before competitors. The critical timeline for action is immediate, as decisions made in the next 12-24 months will likely determine the sector’s trajectory for the coming decade.

Trade War Impact on Southeast Asia

Before the pause, high US tariffs hit Cambodia (49%), Vietnam (46%), and Malaysia (24%).

These countries benefited from companies diversifying supply chains away from China.

They’re caught between China (import market) and the US (export market) in the trade conflict.

ASEAN economic ministers expressed “deep concern” about US tariffs but won’t impose retaliatory actions

Diplomatic Challenges

China needs to show restraint rather than pressure neighbors for public support.

Xi recently chaired a conference focusing on diplomacy with neighboring countries.

China describes ASEAN as “priority in its neighborhood diplomacy”

Malaysia’s PM Anwar Ibrahim, also serving as ASEAN chair, will aim to present a unified voice

Country-Specific Interests

Vietnam: Exports to the US equal 30% of GDP; offering zero tariffs on US goods to negotiate with Trump

Cambodia: Likely to showcase China-funded Ream naval base expansion and seek funding confirmation for the Funan Techo Canal project

Both countries seek to navigate tensions while protecting their economic interests.

The article suggests Xi will need to demonstrate that China is a reliable partner while respecting that these countries are caught in a difficult position between the US and China in the ongoing trade war.

China’s Regional Influence and Trade Opportunities in Asia

Based on the article and broader context, here’s an analysis of China’s potential to leverage the current geopolitical situation in Asia, including opportunities for regional trade partners and specifically Singapore.

How China Can Leverage the Power Vacuum in Asia

-

- Diplomatic Outreach During Uncertainty

- Xi’s Southeast Asian tour is strategically timed during US tariff disruptions.

-

- China can position itself as a more reliable and predictable partner compared to the fluctuating US trade policies.

- Diplomatic Outreach During Uncertainty

-

- Economic Integration and Dependency

- China can deepen regional economic integration through initiatives like RCEP and BRI.

-

- As the US creates trade uncertainty, China can offer stability through consistent trade frameworks.

- Economic Integration and Dependency

-

- Regional Leadership

- China can strengthen its position as the region’s economic center of gravity.

-

- By supporting ASEAN’s unified response to US tariffs, China positions itself as respecting regional autonomy.

- Regional Leadership

-

- Alternative Trade Networks

- China could accelerate the development of trade and financial mechanisms less dependent on US systems.

-

- Yuan-based trade settlement could provide insulation from US financial pressure

- Alternative Trade Networks

How Asia Can Gain from China Trade

-

- Market Access and Export Diversification

- Asian countries can reduce dependency on the US market by expanding trade with China.

-

- China’s growing middle class represents a massive consumer market for Asian exports.

- Market Access and Export Diversification

-

- Investment in Infrastructure

- China offers infrastructure financing through BRI without the political conditions often attached to Western funding.

-

- This can address critical development needs in many Asian countries

- Investment in Infrastructure

-

- Supply Chain Integration

- Countries can benefit from integration into Chinese supply chains as China moves up the value chain.

-

- This creates opportunities for manufacturing and services sectors in developing Asian economies.

- Supply Chain Integration

-

- Negotiating Leverage

- Strong trade relationships with China give Asian nations better bargaining positions with the US.

-

- This “dual track” approach could result in better trade terms from both powers.

- Negotiating Leverage

How Singapore Can Gain from Strong China Trade Relations

-

- Financial Hub Positioning

- Singapore can strengthen its role as a key financial intermediary for China’s international trade.

-

- Opportunities exist in RMB trade settlement, financing for regional infrastructure projects.

- Financial Hub Positioning

-

- Supply Chain Resilience

- Singapore’s advanced logistics infrastructure makes it valuable as a regional hub amid supply chain disruptions.

-

- Chinese companies may increase investments in Singapore to maintain stable operations.

- Supply Chain Resilience

-

- Technology Collaboration

- Singapore can benefit from joint ventures in emerging sectors like AI, green tech, and digital infrastructure.

-

- Access to China’s massive market for Singapore’s technology firms and startups

- Technology Collaboration

-

- Value-Add Services

- Singapore’s strong legal, financial, and business services sectors can support Chinese companies’ regional operations.

-

- Position as a “neutral” advisory center for both Chinese and Western firms navigating regional complexities

- Value-Add Services

Challenges and Considerations

-

- Balancing Relationships

- Asian countries, including Singapore, must carefully balance China-US relations.

-

- Over-dependency on either power creates vulnerability

- Balancing Relationships

-

- Managing Domestic Concerns

- The influx of Chinese goods could threaten local industries, as noted in the article.

-

- Need for thoughtful trade policies that protect domestic economic interests.

- Managing Domestic Concerns

-

- Sovereignty Concerns

- Countries must ensure that economic dependency doesn’t translate to diminished sovereignty.

-

- The Cambodia example shows potential tensions when a country becomes highly aligned with China.

- Sovereignty Concerns

Singapore’s unique position as both a significant financial hub and a predominantly ethnic Chinese city-state gives it particular advantages in navigating these complex relationships. However, it also requires careful diplomatic balancing to maintain its independence and strategic flexibility.

I’d be happy to discuss this article about the current trade tensions between China and the US. The article draws interesting parallels between China’s current response to Trump’s tariffs and Mao Zedong’s approach during the Korean War.

Key points from the article:

-

- China announced it would match Trump’s tariffs of 125% (later clarified as 145% by the White House) starting April 12, 2025.

-

- Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Mao Ning stated, “China never bluffs – and we see through those who do,” signaling China’s willingness to engage in a trade war.

-

- The article connects this stance to Mao Zedong’s philosophy during the Korean War, particularly his belief that “A well-thrown first punch can prevent 10,000 punches later.”

-

- The Chinese government appears to be invoking the historical narrative of the Korean War (1950-1953) to prepare its population for economic hardship, framing it as a matter of national dignity and resistance against American pressure.

-

- The article notes that some Chinese citizens are concerned about the economic impact, with one quoted as saying, “I’ve been jobless for half a year. If we keep fighting, I’ll have to retire at age 30.”

-

- The spokeswoman has been posting historical Mao quotes on social media, including one calling America a “paper tiger” whose threats shouldn’t be taken seriously.

This piece illustrates how historical narratives and national psychology can shape trade policy and international relations. The Chinese government seems to be framing the current trade tensions through the lens of past conflicts with the US, particularly emphasizing resistance over compromise.

China’s Response to US Tariffs: Analysis and Implications

China’s Response Strategy

China’s matching of the US tariffs at 125% (reported as 145% by the White House) represents a significant escalation in trade tensions. This response reflects several key strategic considerations:

-

- Non-negotiation under pressure: China has explicitly stated it will not negotiate under duress, insisting on talks only on an “equal footing.” This stance is consistent with Chinese negotiating patterns where appearing to yield to pressure is viewed as a weakness.

-

- Historical framing: The Chinese government is drawing on Mao Zedong’s approach during the Korean War, framing the trade conflict as a struggle against American hegemony that requires strength and resilience.

-

- Domestic narrative management: By invoking historical resistance against the US, China is preparing its population for economic pain while framing it as a necessary national sacrifice.

-

- Signal of economic confidence: Despite potential domestic economic costs, China’s willingness to match tariffs signals confidence in its ability to withstand economic pressure.

Implications for World Trade

The immediate matching of high tariffs between the world’s two largest economies will have far-reaching consequences:

-

- Supply chain disruption: Global supply chains built around US- China trade will face significant disruption, forcing multinational companies to reconsider their manufacturing and sourcing strategies.

-

- Acceleration of decoupling: This escalation will likely accelerate the economic “decoupling” between the US and China in strategic sectors like technology, pharmaceuticals, and advanced manufacturing.

-

- Increased regionalization: Trade patterns may increasingly regionalize around separate US and China-centered economic spheres.

-

- Potential WTO challenges: The extreme tariff levels likely violate World Trade Organization rules, potentially further undermining the global trade governance system.

-

- Inflationary pressure: Higher costs for imported goods could contribute to inflation in both markets and globally.

Impact on Asian Economies

The effects will vary significantly across Asian economies:

-

- Supply chain beneficiaries: Countries like Vietnam, Malaysia, and India may benefit from accelerated supply chain diversification away from China.

-

- Commodity exporters: Resource-rich countries supplying China’s manufacturing may face reduced demand if Chinese exports to the US decline significantly.

-

- Regional trade frameworks: Regional trade agreements like RCEP (Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership) may gain importance as alternatives to US-China trade.

-

- Currency fluctuations: Asian currencies may face volatility as trade patterns shift and capital flows adjust to the new trade landscape.

Specific Impact on Singapore

As an open, trade-dependent economy, Singapore faces particular challenges and opportunities:

-

- Trade hub role: Singapore’s position as a regional trade and financial hub means it’s particularly exposed to disruptions in global trade flows.

-

- Re-export impact: Singapore’s re-export business may face challenges as direct US- China trade declines.

-

- Financial services opportunity: Singapore may benefit as companies seek neutral financial and legal environments for transactions that avoid direct US-China engagement.

-

- Supply chain reconfiguration: Singapore’s logistics sector could benefit from companies reconfiguring regional supply chains.

-

- Investment redirection: Singapore may attract increased investment as companies seek stable alternatives to both the US and Chinese markets.

The mutual implementation of extreme tariffs represents a significant escalation in US-China economic tensions with global repercussions. For Asian economies, including Singapore, the challenge will be navigating the disruption while potentially benefiting from the reconfiguration of global supply chains and investment patterns.

Singapore’s Navigation Strategy in the US-China Rift: Projections and Policy Directions

Economic and Business Adaptation

Singapore will likely pursue a multi-pronged approach to navigate the intensifying US-China trade conflict:

Business Policy Projections

-

- Supply Chain Resilience Initiative: Singapore will probably expand government incentives for businesses to diversify supply chains beyond both China and the US, focusing on ASEAN integration and India connections.

-

- Financial Services Positioning: Singapore will likely enhance its reputation as a neutral financial hub by strengthening regulatory frameworks that allow companies to conduct business with both Chinese and American partners without violating either country’s restrictions.

-

- Strategic Sector Development: Expect accelerated investment in sectors less vulnerable to US- China tensions, including green technology, biomedical sciences, and digital services.

-

- SME Support Programs: Singapore will likely create targeted support for small and medium enterprises affected by tariffs, potentially including tax relief and export assistance to help them pivot to new markets.

Labor Market Adaptations

-

- Skills Transformation: Singapore will accelerate upskilling programs in emerging sectors, helping workers transition from manufacturing roles disrupted by trade tensions to growth areas like digital services and green technology.

-

- Immigration Policy Adjustments: Expect careful calibration of foreign talent policies to attract specialized expertise in strategic sectors while addressing domestic concerns about job competition.

-

- Expansion of Safety Nets: Singapore may strengthen social support programs to cushion workers in sectors negatively impacted by the trade conflict.

Diplomatic Positioning

Singapore’s diplomatic approach will reflect its traditional balancing act but with adaptations for the new reality:

-

- Enhanced ASEAN Centrality: Singapore will likely work to strengthen ASEAN’s role as a platform for engaging both powers, advocating for maintaining the region’s strategic autonomy.

-

- Multilateral System Defense: Expect Singapore to become even more vocal in international forums about preserving rule-based trade and security frameworks.

-

- Quiet Diplomacy: Singapore will likely maintain open channels with both powers through high-level dialogues while avoiding public criticism of either side’s trade policies.

-

- Diversified Strategic Partnerships: Beyond the US and China, Singapore will strengthen ties with middle powers like Australia, Japan, South Korea, and India as part of a hedging strategy.

Specific Policy Initiatives

-

- Enhanced Digital Trade Framework: Singapore will likely develop legal and technical infrastructure to position itself as a trusted neutral digital hub for international commerce.

-

- Strategic Resource Security: Expect increased investment in food, water, and energy security to reduce vulnerability to supply chain disruptions.

-

- Expanded Third-Country Collaboration: Singapore may promote “third-country” business models in which Singapore companies facilitate US-China commercial interaction through neutral platforms.

-

- Education and Research Strategy: Singapore’s universities and research institutions will carefully manage collaborations with both American and Chinese institutions, maintaining access to innovation while navigating increasing restrictions on technology transfer.

Core Principles of Singapore’s Approach

Throughout these adaptations, Singapore will maintain its fundamental principles:

-

- Pragmatic Non-Alignment: Singapore will resist pressure to choose sides while maintaining relationships with both powers.

-

- Rules-Based Advocacy: Singapore will consistently advocate for international norms and legal frameworks rather than power-based solutions.

-

- Economic Openness: Singapore will defend free trade principles while adapting to a more fragmented global economy.

-

- Long-Term Perspective: Policy responses will reflect Singapore’s traditional approach of planning for long-term sustainability rather than short-term advantage.

Singapore’s relatively small size, combined with its strategic location and developed economy, creates both vulnerability and opportunity in the US- China rift. Its response will likely demonstrate the same pragmatism and forward thinking that has characterized its approach to previous international challenges. However, the intensifying superpower competition presents unprecedented tests to this strategy.

Strategic Solutions for Singapore

Singapore can consider several approaches to mitigate these challenges:

- Diplomatic engagement: Continue emphasizing Singapore’s trade deficit with the US and long-standing partnership in security and economic matters.

- Trade diversification: Accelerate efforts to develop alternative markets, particularly within ASEAN, India, and other trade agreement partners.

- Strategic industry positioning: Focus on sectors where Singapore offers unique value propositions that American buyers cannot easily replace (specialized manufacturing, advanced services).

- Value chain upgrades: Move further up the value chain in key industries to create products and services where price sensitivity is lower and tariff impacts can be absorbed.

- Digital economy development: Accelerate digital service exports, which may be less affected by physical goods tariffs.

- Regulatory optimization: Create even more business-friendly environments to attract companies looking to restructure their Asian operations in response to the changing trade landscape.

- Innovation focus: Double down on R&D investments to develop proprietary technologies and products that maintain market access despite tariff barriers.

Long-Term Economic Projections

If current policies continue, economic models suggest:

-

- A potential 1-3% reduction in Singapore’s direct exports to the US in the short term.

-

- Gradual adaptation over 2-3 years as supply chains adjust.

-

- Moderate but manageable impact on overall GDP (likely less than 0.5% drag on growth).

-

- Possible acceleration of Singapore’s economic integration with non-US markets, particularly within Asia.

-

- Potential opportunities emerging from repositioning as companies restructure their global operations to navigate the new tariff landscape.

The resilience of Singapore’s economy, its diversified trade relationships, and adaptable business environment suggest that while disruptive, these tariff policies are unlikely to cause severe long-term damage if Singapore implements strategic adaptations effectively.

Singapore’s Diplomatic and Supply Chain Solutions in ASEAN

Diplomatic Strategy Projections

Singapore can leverage its position within ASEAN to develop diplomatic solutions that mitigate Trump’s tariff:

-

- ASEAN Collective Bargaining: Singapore could lead ASEAN in forming a unified response to US tariff policies, increasing negotiating leverage by representing a more significant economic bloc.

-

- Strategic Mediation Role: Position Singapore as a neutral mediator between US and China trade tensions, potentially creating exemptions or special status for intermediary hubs.

-

- Sectoral Cooperation Agreements: Pursue targeted agreements in strategic sectors like semiconductors, biotech, and digital services where Singapore and ASEAN have competitive advantages.

-

- Multilateral Forum Leadership: Strengthen Singapore’s voice in WTO and other multilateral bodies to challenge protectionist policies through established dispute resolution mechanisms.

-

- US-ASEAN Business Council Engagement: Work through established bodies to maintain dialogue with US business interests that benefit from trade with Singapore.

Labor Market Adaptations

- Singapore faces unique labour challenges that require ASEAN-focused solutions:

- =Regional Talent Integration: Develop expedited work permit programs for skilled ASEAN workers in sectors affected by tariff-induced restructuring.

- Cross-Border Training Initiatives: Create joint Singapore-ASEAN training programs to develop specialized workforces for industries positioning to bypass tariff impacts.

-

- Digital Workforce Development: Accelerate upskilling programs focused on digital economy roles that are less affected by physical goods tariffs.

- Research Collaboration Networks: Establish cross-border research teams focused on developing technologies and processes that maintain competitiveness despite tariffs.

- Industry 4.0 Transition Support: Joint programs with ASEAN partners to help traditional manufacturing sectors transition to more automated, higher-value production methods.

Supply Chain Reconfiguration

Singapore can work within ASEAN to restructure supply chains for resilience:

-

- ASEAN Content Integration: Strategically increase ASEAN-sourced components in export products to leverage existing Free Trade Agreements (FTAs).

-

- Rules of Origin Optimization: Work with ASEAN partners to harmonize and optimize rules of origin definitions to maximize FTA benefits.

-

- Regional Distribution Hub Enhancement: Strengthen Singapore’s position as an intra-ASEAN distribution center, reducing dependence on US markets.

-

- Complementary Manufacturing Networks: Develop coordinated manufacturing ecosystems where production steps are strategically allocated across ASEAN countries to optimize tariff outcomes.

-

- Supply Chain Digitalization: Lead ASEAN initiatives to digitalize supply chains, improving visibility and enabling more agile responses to tariff changes.

-

- Strategic Stockpiling Coordination: Develop regional approaches to inventory management that reduce vulnerability to sudden policy shifts.

-

- Alternative Shipping Routes: Invest in logistics infrastructure that reduces dependence on routes vulnerable to geopolitical disruption.

Practical Implementation Timeline

Short-term (0-12 months):

-

- Initiate high-level diplomatic dialogues within ASEAN

-

- Begin labor market assessment for cross-border talent sharing

-

- Establish task forces for supply chain vulnerability analysis

Medium-term (1-3 years):

-

- Implement the first wave of coordinated ASEAN manufacturing networks

-

- Launch regional workforce development programs

-

- Develop digital infrastructure for integrated supply chains

Long-term (3-5 years):

-

- Establish fully functional regional value chains less dependent on US markets

-

- Create sustainable talent mobility frameworks within ASEAN

-

- Position Singapore as the key node in a more self-sufficient ASEAN economic ecosystem

These projections suggest that Singapore can mitigate tariff impacts and potentially emerge stronger by deepening integration with ASEAN partners and developing more resilient regional economic structures.

Singapore’s Response Strategy

Singapore has established a high-level national task force chaired by Deputy Prime Minister Gan Kim Yong to navigate this crisis. This approach demonstrates:

-

- Institutional seriousness – By forming a task force comparable to their COVID-19 response mechanism, Singapore signals they view these tariffs as a potentially severe economic threat

-

- Collaborative governance – The task force integrates government economic agencies with business federations and labor unions, showing a whole-of-society approach

-

- Rapid mobilization – The swift formation of this group following Trump’s April 2nd “Liberation Day” tariff announcements shows Singapore’s characteristic preparedness.

Prime Minister Lawrence Wong’s stark declaration that “the era of rules-based globalisation and free trade is over” represents a significant rhetorical shift for a nation that has long championed and benefited from open global trade.

Economic Impact Analysis

The article identifies several key economic impacts:

-

- Labor market disruption:

- Potential boost to domestic industries and reshoring activities

- Vulnerability in export-dependent sectors

- Risk to contract workers and those in trade-related industries

-

- Possible wage restraint and reduced bonuses

- Labor market disruption:

-

- Supply chain challenges:

- Potential restructuring of pharmaceutical and semiconductor supply chains

- Companies front-loading components and stockpiling inventory as precautionary measures

-

- Operational challenges as businesses attempt to diversify supply sources

- Supply chain challenges:

-

- Price effects:

- Possible disinflationary pressure if Chinese exports are redirected to non-US markets

- Construction sector facing cost volatility in materials like steel and timber

-

- Risk of higher consumer prices as supply chain inefficiencies build

- Price effects:

-

- Growth prospects:

- Likely downgrading of GDP forecast from 1-3% to possibly 0-2%

- Risk of postponed business investment due to uncertainty

-

- Potential contraction in consumer confidence and spending

- Growth prospects:

Diplomatic Implications

This situation represents a significant diplomatic challenge for Singapore:

-

- Navigating great power tensions:

- Singapore must maintain relationships with both the US and China while these powers engage in escalating trade conflicts

- Navigating great power tensions:

-

- The 10% tariff on Singapore exports (described as “relatively mild” compared to regional peers) suggests Singapore still maintains a favorable status with the US despite its close economic ties with China

-

- Regional repositioning:

- The article notes Singapore will likely work to “strengthen relationships with friendly partners” within ASEAN

- Increased focus on alternative trade frameworks that exclude the US: CPTPP, RCEP, BRICS+

-

- Opportunity to position Singapore as a stabilizing regional force amid volatility

- Regional repositioning:

Diplomatic identity shift:

-

- Singapore faces an existential challenge to its longstanding identity as a champion of rules-based global trade

-

- Singapore must develop a new diplomatic narrative that acknowledges protectionism while preserving Singapore’s core economic interests

-

- Will need to balance being a critic of protectionism while avoiding antagonizing major trading partners

Policy flexibility:

-

- Singapore retains significant policy flexibility with possible monetary easing through S$NEER adjustments

-

- Fiscal room remains to support businesses and households if conditions deteriorate

-

- The government appears ready to implement targeted interventions rather than wholesale economic restructuring

Long-term Strategic Implications

The situation forces Singapore to accelerate several strategic adaptations:

-

- Economic diversification beyond traditional export markets and sectors

-

- Workforce development focused on resilience and adaptability.

-

- Social safety net enhancement to protect vulnerable citizens during economic volatility

-

- Diplomatic reorientation toward a more complex, less rules-based international order

PM Wong’s framing of this as “a profound turning point” signals that Singapore views this not as a temporary disruption but as a fundamental shift in the global economic architecture that will require sustained strategic adaptation.

Analysis of IT Security Workforce Impact in Singapore’s Tariff Response Context

While the article doesn’t directly address IT security workforce implications, I can analyze likely impacts based on the broader economic and security context Singapore faces amid these trade tensions.

Immediate IT Security Workforce Implications

-

- Workforce pressure points:

- Singapore already faces IT security talent shortages (like most global markets)

- Economic uncertainty might paradoxically both increase demand for security expertise while constraining hiring budgets

-

- Contract security workers may face the dual pressure of increased workloads and employment instability

- Workforce pressure points:

Strategic Security Workforce Considerations

-

- Digital sovereignty concerns:

- The breakdown of “rules-based globalisation” likely extends to digital infrastructureSingapore may accelerate efforts to develop sovereign cybersecurity capabilities less dependent on US or Chinese technologies.

-

- This could drive investment in local security talent development and retention.

- Digital sovereignty concerns:

-

- Supply chain security expertise:

- Growing need for specialists who understand both cybersecurity and supply chain logisticsCompanies restructuring global operations will need security experts who can assess third-party risks across diverse regulatory environment.s

-

- May create premium demand for security professionals with international experience

- Supply chain security expertise:

-

- Critical infrastructure protection:

- Singapore’s position as a trade and financial hub makes its digital infrastructure an even more critical national asset during trade disputes

-

- Could accelerate government investment in security workforce development for critical sectors

- Critical infrastructure protection:

Workforce Development Responses

-

- Targeted training initiatives:

- The national task force may incorporate IT security workforce development into its mandate

- Existing initiatives like Singapore’s Skills Framework for ICT may be expanded with security-specific components

-

- Public-private partnerships for security training could intensify

- Targeted training initiatives:

-

- International talent attraction:

- Economic disruption in other markets might create opportunities for Singapore to attract displaced security talent

-

- Immigration policies might be adjusted to facilitate security talent.

- International talent attraction:

-

- Security automation investment:

- Labor constraints and economic pressure could accelerate the adoption of security automation technologies

-

- Creates demand for higher-skilled security professionals who can manage automated systems

- Security automation investment:

Broader Implications

-

- Security as an economic differentiator:

- Strong cybersecurity capabilities could become a competitive advantage for Singapore amid global supply chain restructuring

-

- Companies may relocate sensitive operations to Singapore precisely because of its security reputation and workforce

- Security as an economic differentiator:

-

- Geopolitical security considerations:

- IT security professionals increasingly need to understand geopolitical tensions and their technology implications

-

- Security workforce development may incorporate more training on navigating divided technology ecosystems.

- Geopolitical security considerations:

-

- Resilience focus:

- Aligns with PM Wong’s emphasis on adaptability and resilience as key values

-

- IT security workforce likely to place greater emphasis on business continuity and resilience planning rather than just threat prevention

- Resilience focus:

The national task force will likely need to address IT security workforce development as part of its broader mandate to strengthen Singapore’s economic resilience in this new trade environment.

Analysis of Relevant WSQ Programs for IT Security Workforce Development

In Singapore’s current context of responding to trade tensions and economic uncertainty, several Workforce Skills Qualifications (WSQ) programs are directly relevant to developing IT security talent. These programs would be particularly valuable as Singapore looks to strengthen its cybersecurity capabilities during this period of global economic realignment.

Key Relevant WSQ Programs

-

- Skills Framework for Infocomm Technology (SF for ICT)

- Includes dedicated cybersecurity career tracks with structured progression paths

- Offers certification in cybersecurity operations, governance, and architecture

-

- Particularly relevant for retraining professionals from other sectors impacted by trade disruptions

- Skills Framework for Infocomm Technology (SF for ICT)

-

- Advanced Certificate in Infocomm Technology (Security)

- Provides foundation-level security training for IT professionals

- Covers network security, cryptography, and security operations

-

- Could help rapidly expand the security talent pipeline if prioritized by the task force

- Advanced Certificate in Infocomm Technology (Security)

-

- Professional Diploma in Cybersecurity

- More comprehensive program covering both technical skills and security governance

- Includes modules on risk management particularly relevant to supply chain security

-

- Could be targeted at mid-career professionals needing to pivot as job markets shift

- Professional Diploma in Cybersecurity

-

- Specialist Diploma in Cybersecurity Management

- Focuses on strategic security planning and management

- Particularly relevant for developing leaders who can navigate security challenges in a volatile trade environment

-

- Includes modules on regulatory compliance across different jurisdictions

- Specialist Diploma in Cybersecurity Management

-

- Critical Infocomm Technology Resource Programme Plus (CITREP+)

- Provides funding support for professionals to obtain industry certifications

- Could be expanded or prioritized as part of the task force’s workforce development strategy

-

- Particularly valuable for quickly addressing specific security skill gaps

- Critical Infocomm Technology Resource Programme Plus (CITREP+)

Strategic Integration Opportunities

These WSQ programs could be strategically augmented to address specific challenges related to the current trade situation:

-

- Supply Chain Security Modules

- Adding specialized content on securing reconfigured supply chains

-

- Developing competencies in third-party risk assessment relevant to new trading partners

- Supply Chain Security Modules

-

- Digital Sovereignty Components

- Incorporating training on building resilient systems less dependent on potentially restricted technologies

-

- Developing skills for operating in increasingly fragmented technology ecosystems

- Digital Sovereignty Components

-

- Critical Infrastructure Protection

- Enhancing training specific to Singapore’s critical financial and logistics infrastructure

-

- Focusing on resilience in the face of both economic and security pressures

- Critical Infrastructure Protection

Implementation Considerations

For maximum effectiveness, the national task force could consider:

-

- Accelerated Funding Mechanisms

- Increasing subsidies for these programs, particularly for workers from vulnerable sectors

-

- Creating fast-track completion options for critical skill areas

- Accelerated Funding Mechanisms

-

- Industry-Specific Customization

- Tailoring program components to address the security needs of particularly vulnerable industries

-

- Developing specialized tracks for financial services, logistics, and manufacturing security

- Industry-Specific Customization

-

- Integration with Economic Support Measures

- Linking participation in these programs with broader business support initiatives

-

- Using workforce development incentives to encourage security investment during economic uncertainty

- Integration with Economic Support Measures

These WSQ programs represent established frameworks that could be rapidly scaled and adapted to address the security workforce needs emerging from Singapore’s current economic challenges.

Maxthon

This meticulous emphasis on encryption marks merely the initial phase of Maxthon’s extensive security framework. Acknowledging that cyber threats are constantly evolving, Maxthon adopts a forward-thinking approach to user protection. The browser is engineered to adapt to emerging challenges, incorporating regular updates that promptly address any vulnerabilities that may surface. Users are strongly encouraged to activate automatic updates as part of their cybersecurity regimen, ensuring they can seamlessly take advantage of the latest fixes without any hassle.

This meticulous emphasis on encryption marks merely the initial phase of Maxthon’s extensive security framework. Acknowledging that cyber threats are constantly evolving, Maxthon adopts a forward-thinking approach to user protection. The browser is engineered to adapt to emerging challenges, incorporating regular updates that promptly address any vulnerabilities that may surface. Users are strongly encouraged to activate automatic updates as part of their cybersecurity regimen, ensuring they can seamlessly take advantage of the latest fixes without any hassle.

Maxthon has set out on an ambitious journey aimed at significantly bolstering the security of web applications, fueled by a resolute commitment to safeguarding users and their confidential data. At the heart of this initiative lies a collection of sophisticated encryption protocols, which act as a robust barrier for the information exchanged between individuals and various online services. Every interaction—be it the sharing of passwords or personal information—is protected within these encrypted channels, effectively preventing unauthorised access attempts from intruders.

In today’s rapidly changing digital environment, unauthorised commitment to ongoing security enhancement signifies not only its responsibility toward users but also its firm dedication to nurturing trust in online engagements. With each new update rolled out, users can navigate the web with peace of mind, assured that their information is continuously safeguarded against ever-emerging threats lurking in cyberspace.